Krista Alikas, Tartu Observatory

November 2017

Inland waters represent a wide range of optical water types that can vary a lot between different lakes and often even inside one lake.

Figure 1. Ilmar Ansko (Tartu Observatory) performing the radiometric measurements on the Valguta Mustjärv (660 m x 470 m) in Estonia.

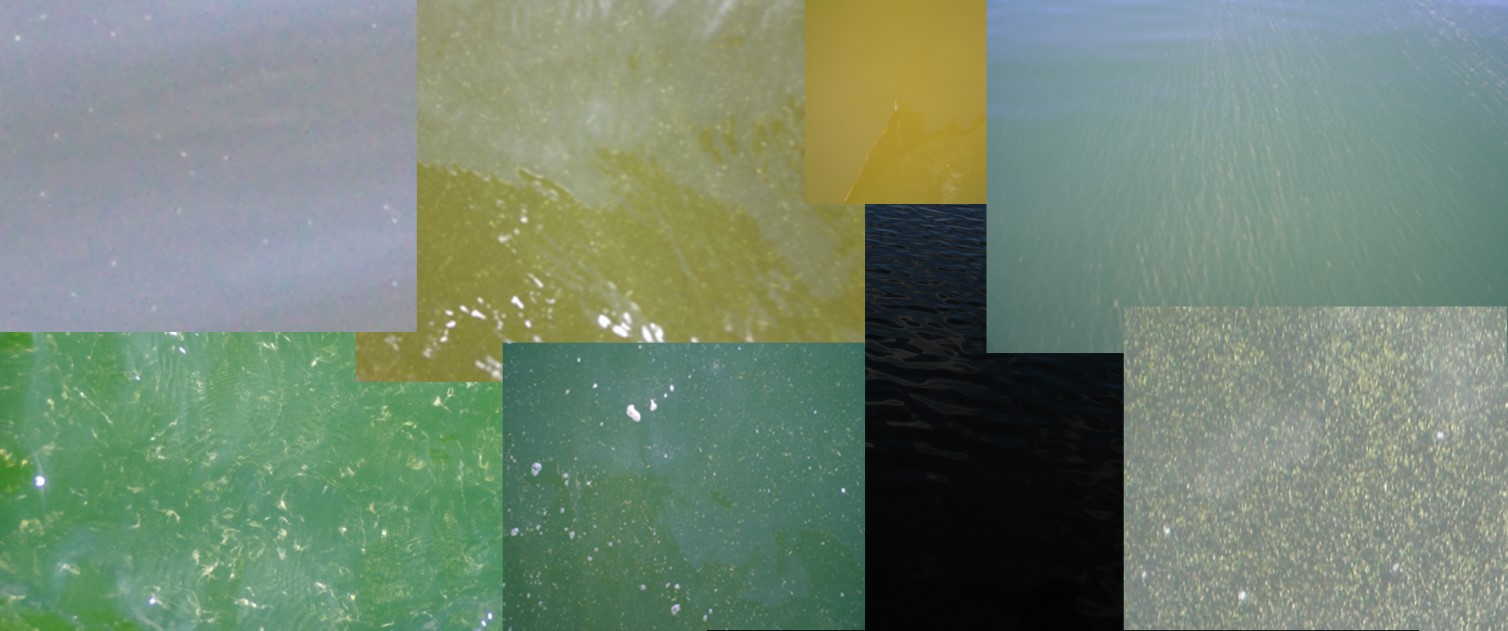

Signals measured by radiometers can be very different and pronounced in different spectral regions. The variable amount of optically active substances results in different optical signatures which determine the colour of the water that can be very variable for inland waters (Fig.2).

Figure 2. Examples of different optical water types. Source Tartu Observatory (TO) field work image collection.

Amounts of all optically active substances in inland waters can be a magnitude higher than usually present in oceanic waters. In addition to the molecular water, the optical properties are determined by phytoplankton, mineral particles and dissolved organic matter. As there can be already variability inside one component (e.g. different groups of phytoplankton), the wide and independent variation of the substances add to the optical complexity.

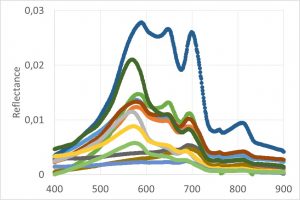

Figure 3. Collection of in situ measured remote sensing reflectance over Estonian inland waters. Source: TO water remote sensing database.

As the presence of the abundant suspended sediments and phytoplankton are still a challenge for the atmospheric correction algorithms, the strong absorption by organic matter may result in the signal from the water around zero in the visible region of spectrum with measurable signal only from 700 nm onwards (Fig.3).

The optical complexity highlights the need to acquire quality controlled measurements with associated uncertainties which can be used to validate the satellite data and estimate its uncertainties over wide range of conditions. Due to accessibility constraints, the in situ monitoring is often performed from small boats or boat-like equipment opposite to more stable platforms featured in previous web stories over oceanic and coastal waters.

The low height of the radiometer above the water surface in combination with possibly spatially inhomogeneous patterns (i.e. phytoplankton surface bloom, stripes of foam, mixture of different optical water masses, waves) will add to the uncertainties of the measurements (Fig.4). Also, the time at measurement stations is much shorter compared to oceanic cruises as the profile for the in water optical measurements can already end at about 1 meter below the surface (or even less) as there is no light to be measured anymore at deeper depths.

Figure 4. The uncertainties can be associated with environmental effect (bottom vegetation, macrophytes, bottom reflection, adjacency effect, Sun glint, clouds, shadows) and with measurement techniques. Source TO field work image collection.

There is no unified method or protocol for radiometric measurements and derivation of the biogeochemical parameters from in situ collected water samples over inland waters. It is possible that measurements can yield to different results in case of same optical properties. The LCE-2 event focused on radiometric measurements under controlled conditions in the laboratory and outdoors in order to analyse the capability of radiometers to produce coincident results. The results of the exercise will show how the uncertainty is increasing by moving from well-controlled conditions (i.e. the lab calibration and indoor exercises) towards realistic field conditions. This knowledge is essential while producing inland water validation datasets for Earth Observation data.

The constantly growing missions of Sentinel series satellites allow to exploit the high temporal and spatial coverage of Earth Observation data to monitor the water quality over inland and coastal waters (Fig.5) with repeatability that would not be feasible with conventional monitoring methods.

Figure 5. Sentinel-2/MSI RGB image from 4th August 2015 is a good illustration of various optical water types present in Estonian inland and coastal waters.

The Sentinel data is essential for developing suitable water quality algorithms for various optical properties which in turn support the assessment of the past and present state of the aquatic ecosystems and their role to the nutrient and carbon cycles. Monitoring and understanding of physical, chemical, biological status of inland and coastal waters is one focus of monitoring agencies and the public and is the subject of several directives e.g. European Water Framework Directive, European Marine Strategy Framework Directive, Bathing Water Directive and regional conventions e.g. HELCOM, OSPAR. Systematically acquired and validated derived satellite products with associated uncertainty evaluation can provide invaluable input for deriving reliable water quality parameters from regional to global scales.

Figure 6. Scientists – always together for better or worse. Source: TO field work image collection.